Sustainability¶

Introduction¶

In a world where population is increasing and emerging third world economies are trying to industrialize we need to concern ourselves with sustainability. Sustainability is defined as the ability to continue a behavior indefinitely. To start with one of the big problems that need to be dealt with soon is CO2 emissions. In particular, according to the U.S. Green Building Council buildings were responsible for 39% (2236 million metric tons) of total U.S. CO2 emissions in 2004 and they are projected to emit about 20% more this year than they did in 2004. The main source of CO2 emissions is energy consumption. With respect to buildings these emissions come from extraction of raw materials, processing, manufacturing, transportation, construction, operation, repair, and finally the building's demolition. Over the next generation the volume of the built space in the world is expected to double.

Over the a 50 year life cycle of a traditional building, 80% to 85% of the total energy it consumes is its operational energy. However, as designs are becoming more and more energy efficient the energy that goes in the the creating of the building is becoming a greater portion of that total energy consumption. This energy that make up that initial embodied energy includes the extraction of raw materials, processing, manufacturing, transportation, and its construction.

Over the a 50 year life cycle of a traditional building, 80% to 85% of the total energy it consumes is its operational energy. However, as designs are becoming more and more energy efficient the energy that goes in the the creating of the building is becoming a greater portion of that total energy consumption. This energy that make up that initial embodied energy includes the extraction of raw materials, processing, manufacturing, transportation, and its construction.

To reduce the embodied energy of a building several techniques are being employed. These include the use recycled material, sourcing material locally, and making use of more energy efficient construction practices. The first two of these are part of what is known as “resource-conscious design” and are central points to sustainable construction. The general goal of sustainable construction is to minimize the natural resource consumption and the impact on ecological systems. To do this products are selected that minimize solid, liquid and gaseous waste. Additionally these products should be easily disassembled at the end of their life, as well as be capable and worth of being recycled.  Finally the inevitable waste that results should be nontoxic to biological systems.

Finally the inevitable waste that results should be nontoxic to biological systems.

This is a complicated subject and entire courses are taught on it at the graduate level. Right now I am mainly introducing you to the nomenclature and the broad concepts. For now let's move on to Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs).

Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) and Life-Cycle Cost¶

An EPD® (Environmental Product Declaration) is an independently verified and registered document that communicates transparent and comparable information about the life-cycle environmental impact of products.

Having an EPD® for a product does not imply that the declared product is environmentally superior to alternatives — it is simply a transparent declaration of the life-cycle environmental impact. (source: EPD website)

In other words EPD is an ecolabel based on life-cycle cost of a product. Life-cycle cost is a way to use economic analysis to select between alternatives based on the cost of a product throughout its life. That is a little circular so let me try again. If you are picking between a car that costs \$20,000 and one that costs \$25,000 and you find out that the cheaper one has an expected annual fuel and maintenance cost of \$7,000 while the \$25,000 car only costs \$4,000 annually, since it is a hybrid. With a little quick thousand dollar math,

$$1,000\times\left(\$20 + \frac{\$7}{\text{year}} \times t \right)= cost_A$$$$1,000\times\left(\$25 + \frac{\$4}{\text{year}} \times t \right)= cost_B$$The break even point $t$ (in years) occurs when $cost_A = cost_B$. $$1,000\times\left(\$20 + \frac{\$7}{\text{year}} \times t \right)= 1,000\times\left(\$25 + \frac{\$4}{\text{year}} \times t\right)$$

Divide both sides by $1,000$... $$\$20 + \frac{\$7}{\text{year}} \times t = \$25 + \frac{\$4}{\text{year}} \times t$$

Rearrange so like terms are on the same sides... $$\frac{\$7}{\text{year}} \times t - \frac{\$4}{\text{year}} \times t = \$25 - \$20$$

Simplify solve for t... $$\left(\frac{\$7}{\text{year}} - \frac{\$4}{\text{year}}\right) \times t = \frac{\$3}{\text{year}} \times t = \$5$$ $$ t \times \frac{\$3}{\text{year}} \times \frac{\text{year}}{\$3} = \$5 \times \frac{\text{year}}{\$3}$$

Cancel out like terms... $$t = \frac{\$5}{\$3}\times \text{year} = \frac{5 \times \$1}{3 \times \$1} \text{years}$$ $$t =\frac{5}{3} \text{years} = 1 \frac{2}{3} \text{ years} = 20 \text{ months}$$

You can see that if you own the car for more than 20 months you'll spend less money by owning the \$25,000 car. At the 2 year mark you would have spent $1,000\times(\$20+\frac{\$7}{\text{year}}\times 2 \text{ years}) = \$34,000$ on the $\$20,000$ car and $1,000\times\left(\$25 + \frac{\$4}{\text{year}} \times 2 \text{ years} \right)= \$33,000$ on the $\$25,000$ car, or about $\$1,000$ less.

This is a simplified example; I assumed the purchase price is the real cost of initial embodied energy. EPD accounts for the impact of raw material extraction to final disposal, and everything in between that needs to be included. Because of the complicated nature of determining this is relatively new in the United States. It is fairly well established in Europe, but it was just since 2001 that the American Center for Life Cycle Assessment (ACLCA) was formed with the intent to provide EPDs in the United States.

Carbon Footprint Index (CFI)¶

CFI is an improvised approach which evaluates the performance of global warming effect for a given building project as a result or consequences of waste generation during construction phase. This analysis tool can be applied for future building projects in assessing environmental performance, thus, affecting waste management practice and improving awareness of waste minimization among construction players. (source: Carbon Footprint Index: A Simplified Tool For Impact Assessment of Construction Waste Generation)

(FYI that source's title is an excellent description of CFI.)

For a building the carbon footprint (not the same as carbon footprint index) is calculated based on two contributing sources, embodied carbon and operational carbon. The embodied carbon comes from the carbon released from the initial embodied energy of the building, the carbon released from the energy required to do maintenance, the disassembly of the building, and the carbon release from decomposition of the waste. The operational carbon only comes from the carbon released due to the energy of operation of the building.

The carbon footprint was developed as a way to estimate the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions due to any manufactured product or activity. It doesn't account for any other toxins like heavy metal contamination or any other regular pollution.

Carbon Footprint Index evaluates the global warming effect for a given building project as a result of waste generation during the construction phase. In this regard it has a much, much, smaller scope than the overall carbon footprint. To calculate the CFI you first need to know the carbon foot print of the construction waste.

$$CF = W \times GWP$$where:

- $CF$ - Carbon footprint ($kg \text{ (of CO}_2\text{)}/ \text{metric ton} $)

- $W$ - Wastage in metric tons ($tonne$)

- $GWP$ - Global Warming Potential ($kg$ of CO$_2$) found in a Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

- $CFI$ - Carbon footprint index ($kg \text{ (of CO}_2\text{)}/ m^2$ )

- $GFA$ - Gross Floor Area ($m^2$)

The typical values for conventional projects CFI range between $21 – 26 kg \text{ (of CO}_2\text{)} /m^2$. The main contributing factors to the CFI of a project are the construction method, waste management and building design. The types of project that score low using CFI are ones that rely heavily on prefabrication in off-site, controlled environments, and then simple assembled the building from the components. An example of this type of technology is prestressed concrete.

I won't be asking you to do these calculations in this course but you should be aware of them for future courses.

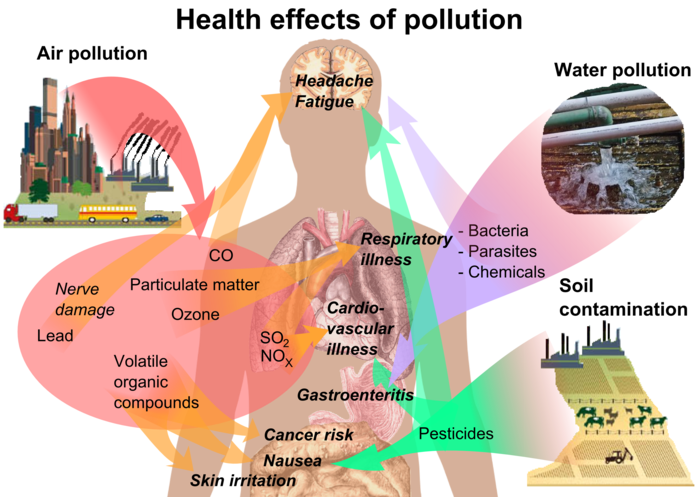

Volatile Organic Compound (VOC)¶

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are organic chemicals that evaporate at room temperature from any material containing them. Some sources include paint, glues, solvents, wood preservatives, aerosol sprays, cleaners and refrigerants. VOCs are numerous and include both human-made and naturally occurring chemical compounds. In building construction many VOCs tend to be dangerous to human health or harmful to the environment. These are regulated by law since concentrations can build up indoors. Harmful VOCs are generally not lethal in low concentrations, but long-term exposure can lead to adverse health effects.

One commonly used example of a VOC is formaldehyde. Formaldehyde can be quite toxic in high concentrations. Because of this, the inclusion of it in building materials is closely regulated. You may have even heard of problems with laminated flooring from China that was sold by Lumber Liquidators that emitted too much formaldehyde.

LEED¶

Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED), is a green building certification program. However LEED is a design tool and not a a tool to measure performance. Although it contains elements of climate-specific aspects it is not solely based on low environmental impact. This has lead to some builders and designers gaming the rating system to achieve LEED certification which in turn increases the economic gains from a building's sale or rental. Since energy conservation is expensive, in the past builders have minimized the points from those categories and maximize points from categories like Sustainable Sites, Location and Transportation, Materials and Resources, and Indoor Environmental Quality. Because of this, LEED designs can be less than the most site- or climate-appropriate choice available. To address these concerns the U.S. Green Building Council has made modifications to the LEED requirements to curb this behavior.

Now LEED is one of the more popular certification programs in the U.S. with around 80,000 projects world wide that have either been registered or certified.

In fact, 88 of the Fortune 100 companies are already using LEED. (source: This is LEED)

As a side note Rinker Hall is the first building in the state university system to using LEED.

Cradle to Gate (CTG)¶

Cradle to Gate is another life cycle assessment process. It focuses on just the first parts of the the life cycle, particularly the material extraction and transportation to manufacturing facilities. In the U.S. about 6% of energy consumed goes to the embodied energy of buildings. This includes energy use by equipment to extract raw materials, energy used to ship the raw materials to the manufacturing facilities and the manufacturing process itself. By designers specifying construction materials with low CTG the total energy consumed by a building is reduced. The information about CTG values is sometimes found on the environmental product declarations (EPD) or business-to-business EDPs.

Summary¶

Again, sustainability is a large topic with whole courses dedicated to it. This should give you a taste of what is out there and maybe some thoughts on what is to come in the future in the building industry. As consumers have started to demand more energy efficiency from buildings and energy prices have rose, there has been an increasing demand for sustainable structures. Since these structures have both real and perceived value, the market for them has been able to demand a higher premium. With climate change in the news more and more, this is only going to become an increasing trend. It is both a good market to be in, and in the long term, a good investment to own.

You need to be aware of new innovations that are going to become more popular as the prices fall: solar panels, for instance. The reported average cost of solar panels in 1977 was \$76.67/watt and in 2014 it is just \$0.613/watt (source) with some people forecasting another 40% price drop over the next two years.

Along with water shortages, innovations in water usage are also on the rise. Recycling grey water for sewage duty will require changes in the design of buildings. Necessitating capture, storage, and potentially treatment in buildings. These will add to initial costs, but could lead to long term savings, and will certainly provide new opportunities in the construction market.

References¶

Github.io version of course website (Do not use this link if you are taking this course in Summer A or B.)

IPython.org (IPython is the opensource software used in the development of much of this course.)

Report any problems¶

Issues Please report any problems that occurred during the viewing of this or any other lecture.

Alternative Reporting - Email damontallen@gmail.com